THE LAST OF THE ALPHABET SISTERS

Sarah was born in 1930 in Lansing, Michigan, the third of a set of identical quadruplets.

They were born in the Edward D. Sparrow Hospital. Her parents were Carl Morlok, a 41-year-old unemployed factory worker of German extraction, and Sadie, a 31-year-old nurse.

It was the height of the Great Depression, and her parents were extremely poor.

Sadie had been told she was going to have twins.

The girls were born one month prematurely. When the quads arrived, it was within ten minutes of each other. The doctors thought Sadie might die. “But our mother finally rallied and said, ‘I’m going to take care of all four of them if the good Lord will just let me live’. And that’s what happened.”

Their birth caused national attention. It is believed they were the first recorded identical quadruplets in the world. It was estimated that the odds of this happening were 500,000-1.

Associated Press said, ‘Lansing’s Morlok quadruplets are the most famous group of babies on the American continent.”

Crowds gathered outside the hospital.

A national newspaper held a competition to name the girls. Their mother wanted to call them Jean, Jane, June and Joan – but was persuaded against this by public opinion.

There were twelve thousand entries. The winner was ten-year old Nancy Haynes, co-incidentally the daughter of the surgeon at the hospital who had brought the girls into the world. Her prize was ten dollars.

The chosen names were Edna A, Wilma B, Sarah C and Helen D. The initials of their first name were to reflect the initials of the hospital they were born in – Edward W Sparrow Hospital. Their middle names didn’t stand for anything – they just reflected the order in which they were born.

Lansing loved the publicity. The city gave the family a rent-free home at 1023 East Saginaw Street. So many visitors came to this house that Carl charged 25 cents to see the girls.

On one occasion, two men snatched a couple of the babies and tried to make off with them, until Carl threatened them with his gun.

The Massachusetts Carriage Company sent the family a custom-made baby carriage with four seats.

Businessmen opened bank accounts for each of the girls.

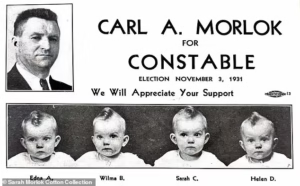

When the girls were just a year old, Carl stood for the elected position of Lansing Constable, even though he had no experience of the police. He used their photograph on his campaign posters with the caption ‘We’d appreciate your support’. He won with a landslide (and went on to be re-elected thirteen times, serving twenty-six years).

The girls were in the press constantly, especially at birthdays or Christmas. The papers nicknamed Carl ‘Jolly Carl’ or ‘Daddy Four-of-a-Kind’. There was even a newsreel of them shown in movie theatres.

Their mother, Sadie, tried to give the quadruplets a normal life. She dressed them in identical clothes and used to take them on long walks in their baby carriage.

It was the era of child stars (e.g. Shirley Temple), so the public attention on the sisters was immense. They were portrayed as the ideal All-American family – everything was picture perfect.

However, behind the scenes, things were very different.

Carl was an abusive man with a vile temper, who used to hit his wife.

He was also a white supremacist. When Sadie was pregnant with what she thought was twins, he shouted at her, saying multiple births only happened to black women. He accused her of low birth.

When Sadie gave birth to the girls, he shouted at her, “Aren’t you a white woman?”

Carl also abused his police position. As the girls grew up, he realised money was to be made from them. He sent them for singing, dancing and piano lessons – all paid for with money taken from police coffers.

At the age of six, Carl sent the girls out on the road as a singing and dancing act. They were called ‘The Morlok Quadruplets’ or sometimes ‘The Alphabet Sisters’.

Their first concert was at a boat show in Lowell, a nearby city. They went down a storm.

After that, they played concerts in Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania, travelling everywhere by train. Their trademark song was ‘Alice Blue Gown’.

Their singing career didn’t make them much money, but Sadie loved the publicity and the attention.

Sarah was asked in later life, when did she know she was famous? She replied, “Well, I think it was in our dancing chorus rehearsal when I glanced to the right, then to the left, and saw three other people who looked just like me, danced like me and sang like me. I think I then realised I was one part of a famous team.”

Meanwhile, things got worse at home. Carl used to bang the girls’ heads together when they wouldn’t go to sleep.

He was a germophobe, so wouldn’t let the girls go to the public library in case they brought back germs on the books.

As they became teenagers, Carl imposed a set of twenty rules. They included no wearing of trousers, no holidays, no friends, no weekend trips, no swimming lessons, no birthday parties, no picnics, no church activities and no boyfriends.

Their mother knitted each one of them a swimsuit in their favourite colour (Sarah’s was yellow), but they were never allowed to wear them.

Carl even took out the internal doors in the house so that he could watch them at all times. He had total control of their lives. Sarah reflected, “We felt like tin soldiers marching to my father’s rules. It was kind of sad growing up. We felt so restricted.”

The girls were told they would never be allowed to get married or have a job.

At high school, they were separated into different classes – Edna with Sarah and Wilma and Helen together. Consequently, Sarah always felt closer to Edna than the others.

During lessons, the girls would swap places, pretending to be each other. The teachers never cottoned on.

During the Second World War, they were used by the media as the perfect example of an American family – this is what you’re fighting for.

The reality was Carl was a Nazi sympathiser, who totally believed in Hitler’s attitude to other races.

The girls were also sexually abused.

Unsurprisingly, by their early twenties, all of the girls were suffering mental health issues, having delusions, seizures or fits. Edna, Wilma and Helen all had electroconvulsive treatment.

Their doctor referred them to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in Bethesda, Maryland. There, Doctor David Rosenthal took the opportunity to make the quadruplets a medical research study.

Their showbusiness days were over.

The study took three years. The girls had countless (unpleasant) physical tests and experiments. Each one of them was assigned their own psychotherapist. Sarah felt hers made a big difference to her, although the others seemed to have no positive effects.

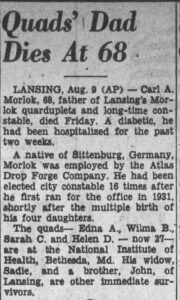

Two years into the study, Carl died.

At the end of the research programme, Sarah left NIMH (the National Institute of Mental Health), although the other three sisters were deemed incapable of living independently, having all been diagnosed with schizophrenia. They were transferred to Northville Psychiatric Hospital, just outside Detroit.

Sarah’s biographer said, “She knew quite clearly that she got better at NIMH and her sisters didn’t – and she always had survivors’ guilt about that.”

Sarah put her recovery down to two factors – a better psychotherapist, and the fact she had been less abused than her sisters.

The report took another three years to come out and was 636 pages long. It concluded their mother was also schizophrenic and their father probably was too. It said the quadruplets, ‘Were victims of an unhappy collusion of nature and nurture’.

Many years later, in the 1980s and 1990s, the other three of the quadruplets were subjected to more tests and experiments, although Sarah refused to participate.

Upon leaving NIMH and no longer subject to her father’s control, Sarah went to college in Lansing and became a legal secretary and accomplished typist.

She also started going to church, becoming a member of an Evangelical Lutheran Church and developed a strong Christian faith.

At the church, Sarah met an air force officer, George Cotton, and they were married soon afterwards.

They were to have three children, Maria, who died at birth, William (Bill), who died of AIDS in 1994, and David.

Soon after David’s birth, George, who suffered mental health issues of his own, left the family.

Sarah came to England to work for a barrister’s business in Newmarket, Suffolk. To do this, she needed special permission from Queen Elizabeth the Second.

From there she moved to Japan, before returning to Lansing to become a notary public.

Her mother, Sadie, died in 1983. Sarah’s biographer, Audrey Clare Farley, later accused Sadie at worst of collusion, at best of ignoring the problems. However, Sarah would not hear a bad word about her mother.

Sarah wrote an autobiography called ‘The Morlok Quadruplets: The Alphabet Sisters’.

Her sister Wilma died in 2002 and Helen the following year – still residents of the psychiatric hospital.

Edna died in 2015.

Sarah’s story only came to light when she was tracked down by writer Audrey Clare Farley, who read an old article about the quadruplets. “She had really faded out of public view.”

Upon meeting her, Audrey was impressed that Sarah could still play 266 songs (hymns and polkas) on the piano from memory.

Audrey was charmed by Sarah, who despite everything, remained proud of what she had achieved as a little girl.

The biography, entitled ‘Girls and their Monsters’, came out in 2023. Audrey described the sisters as having lived in a ‘House of Horrors’.

Audrey said, “Her father was a monster and her mother clearly went along with it to some degree, not least for financial reasons.”

Also in 2023, Sarah’s husband George Cotton died.

Sarah donated seventy Morlok family items to the Edward W. Sparrow Hospital archives. They are now displayed in their Hall of History.

Sarah died in a care home – the last survivor of the Alphabet Sisters.

Her son, David, said of his grandfather (Carl), “He was clearly a devil who exerted such extreme control over his daughters.”

Audrey Clare Farley summed the experience of the quadruplets. “The story of the Morlok sisters is the story of darkness coursing through the world. It is the story of malevolence masquerading as innocence and thereby hiding in plain sight.”

RIP – Research Into Premature(births)